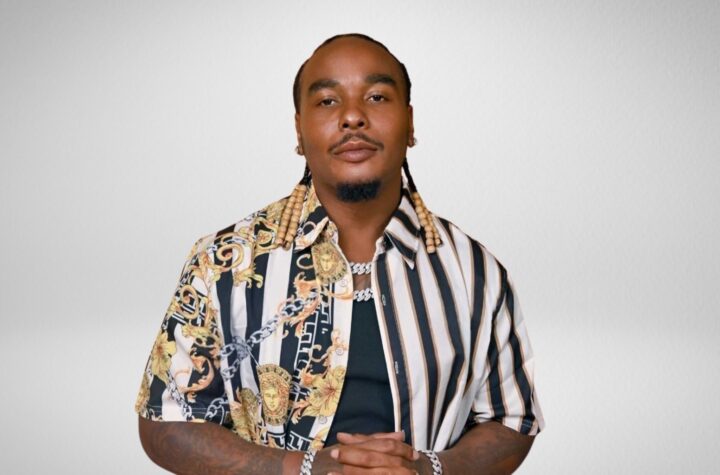

IN THE DOCK: Hero, played by Samuel Adewunmi, has to defend himself in You Don’t Know Me on BBC One (Image: Helen Williams/BBC/Snowed-in Productions)

Last night as I was watching You Don’t Know Me – the BBC One drama based on my debut novel – I looked for the inevitable Scales of Justice statue they always roll out as a short-hand for courtroom drama. It never came. There’s one of these Lady Justice statues – in gold – standing on top of the Old Bailey. And whenever I see her, I say, as if she were an old friend that I’d fallen out with: “You’ve changed, you have.”

She has changed. I can’t see the blindfold any more. And those scales look from here as if they’re being leaned on. But I still love the idea of her. When I started as a criminal barrister 30 years ago, she was pristine and that’s the saddest thing of all.

Equal justice, there in recent memory.The criminal justice system is on a different planet from the days when judges would describe it to juries as “a system that is the envy of the world and exported the world over”. It’s not a phrase you hear much these days.

Today there is a backlog of 60,000 jury trials. And if that weren’t bad enough (and trust me, it is), the criminal legal aid system has been so thoroughly whittled away that even the nub that once was there has gone.

Many experienced criminal barristers have left the legal aid system and hardly any new practitioners go into crime.

It’s not that surprising when the average junior criminal barrister starting out (before tax) gets around £12,000 a year.

Lady Justice on top of the Old Bailey (Image: Graham Barclay/Bloomberg/Getty)

Barristers that remain are working twice as hard, for half the pay. And if you think that’s just life – well, it is, but it comes at a cost. If you’re a criminal practitioner with a legal-aid practice (I’d guess 90 percent are) then you will routinely finish a trial at 4.15pm on a Tuesday and spend the night preparing the next case to start the following morning. And when you finish that case, you’ll pick up the next brief the same day. On legal aid, it’s the only way you survive – the rates are that low. I know because I have done this. Many of my colleagues are doing this. I applaud them. They are superstars functioning by force of will. But I can’t do it any more.

When you’re in it – you run on adrenaline – whether you’re prosecuting or defending. You think on the hoof. You improvise.

You do your best with what you have and all the while you repeat the phrase – “we are where we are” to just about any question you’re asked. Which is just a way of saying it’s too late to do anything more or anything better. If you’re caught up in the net of the justice system, logic and statistics will tell you that you’re likely to be living a life of rank underprivilege.

You might be poorly educated. You might be suffering from mental health issues. You could be unemployed and steeped in poverty. You might have lived a childhood pocked with abuse. You might be in the grip of an addiction caused by some or all of those things.There’s also a good chance (one in four) that you’re from black or Asian minority ethnicity – the stats from the Ministry of Justice are depressing, so I won’t go into them but feel free to have a look.

The reasons for this state of affairs are complex but whatever they are, they are causing a perfect storm and a justice system so acidic that it’s stripping the gold off that Lady Justice.

Some of the top criminal QCs won’t even do legal aid cases any more.

If you’re wealthy you can get yourself a Rolls-Royce of a barrister. I don’t know what the going rate is but I’m pretty sure you won’t get much change out of the cost of an actual Rolls-Royce.The real difference, however, is between those in the middle bracket and everyone else.

They can just about afford to pay fair rates for good work, but it will hurt. It might take their life savings – or another mortgage – but when your freedom is on the line, it seems like it has to be worth it. Even though in a criminal trial you won’t get your legal costs back if you win.

Then there’s everyone else.

When you pay private fees, on the whole you’re not getting anybody better or more skilled or able than you would get on legal aid. Nor would you get anyone who was prepared to work harder.

Hero being searched for forensic evidence (Image: Matt Squire/BBC/Snowed-in Productions)

Because the fact is that your average legal aid barrister, whatever their seniority, is a class act and will work every free hour there is as well as scavenging hours where none are really there to be had.

But what you get on private fees is time. In a private case, I can spend the week before a trial preparing it. On legal aid, I can’t afford to do it because legal aid will not pay for it. I can call my solicitors in a private case and ask questions as and when they arise.

I can organise as many conferences as necessary and, when the case is called for trial, can have my solicitors in court. On legal aid, solicitors are not paid to attend trials any longer and, these days, it’s a rarity to see solicitors there when counsel is instructed. And having solicitors in court is not to be underestimated.

It’s not just a question of having two minds on a job or even having a detailed note of the cross-examination. Solicitors at court are a valuable resource but on legal aid it’s just another missing piece in an ever-more broken bit of machinery.

The result then is twotier justice.

Because although the court always strives to ensure rigorous fairness in every case, what it cannot do is level the playing field. That’s the job of the MOJ through proper and fair legal aid remuneration. But there’s also a third tier. When you earn just above the threshold to be eligible for legal aid but you can’t afford to pay, terrifyingly, you’ll have to represent yourself. Today, more defendants are representing themselves than ever before. Those who do, do it through necessity. Nobody asks to be a defendant.

Nobody wants to be tried. And nobody I have ever met wanted to represent themselves. But what if you had to?

This is the question I circled when I was thinking about my debut novel, You Don’t Know Me. I imagined a defendant who had to act for himself and was forced to write and deliver his own closing speech in a murder case. In the course of writing my book, I began to discover that the disadvantages that such a defendant faced were far more complex and nuanced than those I had first imagined.

The criminal justice system is designed to deal with defendants but isn’t really designed with their active participation in mind.

The system doesn’t want defendants to communicate directly with judges or prosecution barristers. It doesn’t expect defendants to know the law or even to be able to express an opinion on the law. It’s not the court’s fault, or a defendant’s fault, it “is what it is”.

What is happening where you live? Find out by adding your postcode or visit InYourArea

A barrister is there as the bridge between the judge and a defendant or between the jury and a defendant. We make the legal points that best advance the case.

We make the arguments to the jury in language in which they are familiar. We ask questions of witnesses and experts in ways that try to draw out the answers that best serve.We are in familiar territory.

The landscape for us is a fertile and verdant one. But to a defendant acting for himself he’s not just on a different planet from the world he knows… he’s in a different star system.

Nothing there makes sense. The language is alien. The dress is strange and anachronistic. And his position in the dock or out of it is lonely – desolate in fact.

In the novel, I tried to tell the defendant’s story on an emotional rather than on a legalistic level. He wants to tell the jury that they are different, he and they.

Their life experiences are far removed from his. That they must inhabit his skin in order to understand his choices. And then just as he does this and points out the differences, he amplifies the one commonality between their lives and his. Love. That he can be understood through the lens of compassion.

And now, as my novel takes form on the TV screen, I wonder again about this strategy of Hero, my lead character. Hero, played by Samuel Adewunmi, reminds us about the importance of what unites rather than divides.

If governments were able to see defendants in themselves, rather than as aliens, or see the underprivileged as real people linked to them in their humanity, then perhaps we might have a return one day to the principle of equality before law.

And we might begin to operate as though undiverted by wealth, race, privilege and power. We might begin to live blind and, through that, finally begin to see again.

- Imran Mahmood’s new book, I Know What I Saw (Raven, £12.99), andYou Don’t Know Me (Penguin £8.99), are both out now. For free UK P&P on orders over £20, call Express Bookshop on 020 3176 3832 or order via expressbookshop.com

More Stories

Antek’s Lair: A Gripping Tale of Self-Discovery and Resilience Through Adversity

Villa Sans Souci: Unraveling the Mysteries of Florence Nightingale and Malta’s History

Winds of Winter release: George RR Martin declares ‘my head may explode’ in latest setback