Workers constructing the 2022 FIFA World Cup stadiums, the hotels and the new road networks of Qatar call it ‘ciplō mr̥tyu’.

It is a Nepalese phrase meaning the ‘slipping death’ and it is used by labourers preparing the Gulf State for the blue riband tournament in November to describe the sad demise of their colleagues.

Healthy and hard-working, these young men simply slip away in the night.

Migrant workers in Qatar are paid £200-a-month and work in intense heat ahead of World Cup

Workers are at risk of heat exhaustion which can cause people to ‘slip away’ in their sleep

The workers believe their friends’ deaths have resulted from being forced to toil too long under the burning sun without shade, breaks and water in temperatures exceeding 40C for just £8.30-a-day.

They die in their sleep from heat exhaustion, as a result of exploitation.

Since 2010, when FIFA controversially awarded Qatar the 2022 World Cup, more than 6,500 migrant workers have perished in the Middle Eastern country as it has fashioned cities, roads and stadiums out of the desert sand.

With 11 months to go to the opening game, the politicians and the bureaucrats in Qatar and FIFA want to look ahead now, to talk about the tournament, the luxurious stadiums and the changes they have made to labour laws since 2019.

Largest proportion of deaths among migrant workers are recorded as ‘natural causes’

The Gulf state has been blighted by allegations of human rights abuse of construction workers

They want to highlight where working conditions have improved. But before they move on, they have to account for the dead, says Barun Ghimire, a human rights lawyer, who represents migrant workers and their families.

And if they don’t, the dead will haunt the World Cup next year and forever after.

‘It is a blood-stained cup,’ said Ghimire, who lives in Nepal, which has recorded 1,641 deaths of its young citizens in Qatar in the last decade.

Ghimire conjures an obscene image: A sport we love, a show we savour, a competition we hope our country will win, soaked in the blood of those who died to stage it.

And he asks how we as fans can glory in such a spectacle, which will earn FIFA more than £3billion, when it kicks off at the Al Bayt stadium on November 21?

Qatar will host the 2022 World Cup between 21 November and 18 December this year

‘Will we be able to see the World Cup in the same context we used to see it?’ Ghimire asked, speaking to Sportsmail from Kathmandu.

‘If you know the cost of making this beautiful game happen, if you know the sacrifices of the families and those who lost their lives, will you be able to enjoy it?

‘Or if you are a player, would you be able to play with enthusiasm… if it was your country?’

That is the most difficult question England’s players and staff are now going to have to address.

To their credit, the FA have approached the human rights group, Amnesty, and other organisations to brief England players on Qatar. The squad is due to decide its position in talks scheduled for March.

Other national teams have already taken a stand. Norway and Germany wore protest T-shirts ahead of Cup qualifiers this year and Dutch midfielder, Georginio Wijnaldum spoke out on the issue.

Ghimire accepts that people die in huge construction projects, but it is the sheer scale of deaths, their circumstances and the refusal of the Qatari government or FIFA to take responsibility for them that appals him.

Young people from India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Pakistan signed up for Qatar and research by human rights groups has revealed they paid large sums to recruitment agencies, often up to £3,000, to be put to work for a pittance in searing heat and terrible conditions, bonded to their employer with little prospect of escape.

The fact that many have died cannot be disputed. The workers’ own countries keep and publish records of those who perish while working overseas. The Guardian analysed those records to establish the figures.

However, Qatar has failed to record the particulars of the deaths, such as where a person was working when they died, or the details and cause of their passing.

England’s squad will be given presentations on the situation in Qatar ahead of the World Cup

Norway wore t-shirts protesting the human rights record of 2022 World Cup hosts, Qatar

The build-up to the 2022 World Cup in Qatar has been marred by migrant worker deaths

Families rarely know where their loved ones were working and researchers say workers are often shifted from a World Cup project to the supply chain to another construction scheme from one week to the next.

In addition, in seven out of ten deaths of Nepalis, Indians and Bangladeshis the cause is given as ‘natural’. There were no details from a post mortem. The men, it seems, just slipped away. Ciplō mr̥tyu.

As a result, the picture is blurred. How many deaths can be attributed directly to the World Cup? How much blame can be pinned on the competition, and the organisers?

Many immigrants work in gruelling heat throughout the day in order to complete stadiums such as the Education City Stadium (pictured) in time for this year’s tournament

Workers have a designated ‘rest area’ the size of a bus stop during their long day of work

Human rights researchers believe it is a significant proportion, not least because many of the workers were in Qatar precisely because of the country’s successful bid to FIFA.

And those workers had to undergo health screening before taking up their jobs in Qatar, so it is all the more shocking that so many healthy individuals just dropped dead while they were there.

‘They leave the country certified as young and healthy, they are in regular communication with their family and then all of a sudden the family receive the news their husband or son has died,’ said Ghimire.

‘The family ask questions and they are told your son died in his sleep, or we have not been able to identify the cause of death, or it was cardiac arrest.

‘They are not told how their healthy young son was talking to them the day before and died in his sleep that night. It is tragic.’

Unable to legally tie the death to their work, the family also miss out on compensation.

Ghimire believes even now the Qatar Government and FIFA can salvage something from the ruins of so many lives, by at least acknowledging the calamity and injustice.

‘Where does the burden of proof lie? Should journalists have to figure it out? Human rights organisations?’ he asks.

‘Or should a government hosting the World Cup be open about it? The burden of proof is on them.’

Ghimire is pulling no punches. FIFA risks the reputation of its most prized asset – its most lucrative cash cow – if it fails to do right by the dead.

‘If we just move on and act like nothing happened, then the beautiful game is ruined. And not just for this time,’ said Ghimire, who is a football fan himself.

‘A lot of young workers have lost their lives. If that sacrifice is not acknowledged properly, I think the World Cup will be a blood-stained cup… for whoever wins it.’

The contrast between the wealth generated by the World Cup in Qatar and the treatment of those who built the infrastructure is hard to reconcile.

The cost of staging the competition has been estimated at £138billion and FIFA will earn £1.9billion from media rights alone, while migrant workers benefited from a fixed minimum wage introduced this year at just £200 per month.

Lusail Stadium, which will host the 2022 World Cup final, is one of eight being constructed

When a worker dies it not only breaks the heart of their family back home, but can plunge them into poverty. They are left to pay off the loan the paid to the recruitment agency to secure the job in the first place.

Bhupendra Magar, 35, a Nepali had been working on the al-Wakrah stadium, when he died in a labour camp between shifts in May 2018, leaving a wife and two young children.

According to his death certificate, he died from ‘acute respiratory failure’.

‘He was strong and had undergone a medical examination before leaving for Qatar,’ his brother Mohan, told the Guardian after his death. ‘He was just fine.

Migrant workers in Qatar are now entitled to minimum wage of £8.30 per day under new rules

‘The children are still small. He has a wife who doesn’t have an income. It’s hard.’

Qatar’s Supreme Committee told the paper, it investigates all deaths on its sites and in the case of Mr Magar there were no obvious contributing factors, including heat stress.

But Magar’s co-workers knew what it was: ciplō mr̥tyu’. It seems he just slipped away.

Researchers believe heat is a major factor in many deaths. Even now, when Sportsmail visited Qatar last month, we found gangs of workers working in extreme conditions.

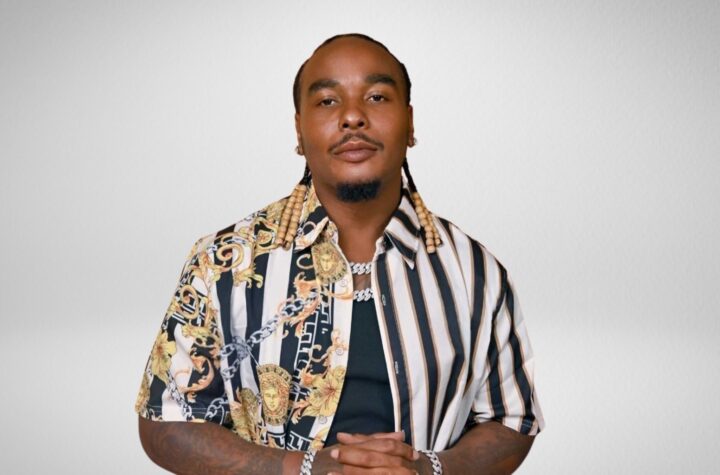

Georginio Wijnaldum has spoken out on the treatment of migrant workers in Qatar

‘In the majority of cases, the Qatar government has significantly failed to provide the cause of death and it is said the Government is not doing a proper autopsy,’ said Rameshwar Nepal, the South Asia director of Equidem Research & Consulting.

Qatar estimates just 37 workers have died on the construction of World Cup stadiums.

Rameshwar admits it impossible to attribute specific deaths to individual projects because of the non-existent records, but he added: ‘Heat exhaustion is definitely a factor in many deaths.’

‘They go to the work; they work in high temperature and they come back to the room in the evening or late at night and the next morning the worker is found dead.

‘There are many workers who are OK but found dead in the morning. There are many cases like that.’

Amnesty has concluded heat stress is a huge risk to workers in Qatar, but the lack of information provided by the Qatari authorities means the number of deaths is ‘unquantifiable’.

More Stories

Rodrigo Bentancur set to return on New Year’s Day as Tottenham are handed a fitness boost

Cristiano Ronaldo had JUST TEN touches during Portugal’s 1-0 World Cup defeat to Morocco

World Cup state-of-play in all eight groups: Tables, fixtures, results, permutations